The biggest Latino director of Summer 2013 talks about Pacific Rim, and his plans for the future in this exclusive conversation

The most surprising thing about Guillermo del Toro is how normal he is. You’d expect one of the most powerful producers and directors in Hollywood, and the man behind some truly bizarre visions like Hellboy and Pan’s Labyrinth, would be different than us–distant, arrogant, special.

In fact, Guillermo del Toro looks like your favorite cousin, or the grown-up geek-boy next door. And he’s one of the nicest men you’ll meet in this industry–open, smart, funny, articulate, and even polite.

Se Fija! Publisher Angela Ortíz and a handful of other Latino journalists had a chance to sit down with him just a few days after seeing his giant robot/giant monster blockbuster Pacific Rim. You can listen to our exclusive audio by clicking on the button below; here are a few choice quotes from their time together (some of them translated from Spanish; Guillermo slipped back and forth between the English and Spanish throughout the interview):

One of the most interesting things about Pacific Rim is that it isn’t just about big robots and big monsters beating on each other. It’s about the people–the humans–who have been affected by their presence, and who join together to fight them. Actors like Charlie Hunnam, Clifton Collins, Jr., and especially Idris Elba were as great to watch as the kujai and jaeger.

“To me it was extremely important to create a movie that was of a piece with the visuals and the human message. The idea behind the entire casting of the film was to show a diversity–not only of diversity of race and color, but of ideology, of the approach to heroism: you can be heroic by being smart, by being a leader, by sacrificing yourself for the good of others. I wanted to try to avoid the sort of WASP ideology: one country, one ideology, one military way to save the world.”

You’ve created some huge and impressive environments in the past, like Hellboy’s New York or the fantasy world of Pan. How did the set for Pacific Rim compare?

“They were the biggest sets I’ve ever had. We took over the Pinewood Studios in Toronto for over a year, and built over 101 sets, all to scale. The set designers studied the geography of every city and town depicted in the film, and it was all very detailed: the steam, the pots, the receipts in the restaurants. Especially the four blocks of Hong Kong that we built. I wanted the audience to recognize places they had been. And of course…they were all destroyed.”

Were the huge robots entirely computerized imagery? Obviously you didn’t build an entire giant robot–though that would have been incredibly cool–but were they all CGI?

“No, I wanted the actors to feel like they were in the middle of everything, especially the shots where you see the large robot heads. We created some machinery to be able to have that feel. One we called ‘Big Moe,” that we could use in wider-angle shots. It was about four floors high and sat in-between the lighting, set, and any machinery. The other one, ‘Little Moe,’ was designed to make quick moves, like fast drops in between set-ups.”

During his remarks before the screening, Guillermo talked about how much he had loved the “kaiju” TV shows of the 1960’s, like Ultra-Man, and wanted to bring some of the sense of wonder he felt as a child back to the imagery.

“The science fiction form in Japan was very varied; the thing about shows like Capt. Ultra or Space Giants or the Ultra series, was the inventiveness. There’s two things that the Japanese do very differently than any other country in the world. One is robots: they don’t have the guilty relationship with technology that we have; they don’t have a warning about technology being bad and coming back to haunt you; they embrace technology with great love, non-judgmentally, and that allows their giant robots to be almost mythical heroes that walk the earth. That’s very unique. And in the giant monsters, it’s almost the same. These monsters are integrated into their daily life; they assign spirits or a guardian or a creature to every element–water, fire–for their daily life; they have benevolent spirits guarding the woods and so forth. And the kaiju, the giant monsters, by extension, are guardians of an almost elemental nature. Godzilla, the first great kaiju, was birthed by Ishiro Honda after World War II, and in many many ways, through Godzilla, Japan was able to heal and come to terms with the tragedies of World War II. And the moment the giant monsters healed the country, the country embraced that monster genre with a passion. Godzilla mutated into a good guy. And then he gave birth to many many other kaiju, including the phenomenon of dai-kaiju, movies where many many kaiju are together. They are loved like national heroes.

“I want people to enjoy and to love these characters and monsters. There’s no chance that a kaiju is going to see this film and say he doesn’t like it and destroy the city. It’s a fantasy and a great way to provoke–in the adult and the child–the wonder and joy of the forces of nature.”

The whole film is a pretty remarkable marriage of ‘human-scale’ drama and special effects. Making those two actually work together, and so successfully, must have been a special challenge.

“Directing effects is a little like directing animation. You need to be involved in everything that looks accidental in the frame; you are provoking everything that happens. I think it was one of the rare movies that ILM was galvanized to do, because the dream of every effects animator is to create either robots or monsters or both of them. And I’m happy to report that we stayed under budget—not on budget, underbudget.”

There are so many incredible images and impressive scenes in Pacific Rim. Are there any that you like the best, or mean the most to you?

My favorite scenes in terms of spectacle and show are the scenes that are called “The Battle of Hong Kong,” which is a 25-minutes huge set piece that starts in the Pacific Ocean and ends in outer space. I don’t think there’s ever been a more spectacular scene in any movie. That is very rewarding for me technically, but from an artistic and personal point of view, the scenes I’m most taken by are the memory of Mako losing everything to an attack in Tokyo. I have this fantastic image of a girl walking with a broken heart, which is a red shoe in her hand. What I did constantly in the movie was to compare the most gigantic with the smallest; for example, in that scene you have a monster that looks like a living temple, gigantic, more than twenty stories high, and you have a little shoe. It’s as close as I get to a fantasy moment in the movie, where a princess is rescued form a dragon by a knight in shining armor. And it changes her life.

How much is the final vision of Pacific Rim–or any of your films–are your own undiluted vision, and how much is the product of a collaborative effort, the result of working with your huge (and often very loyal, long-term) creative team?

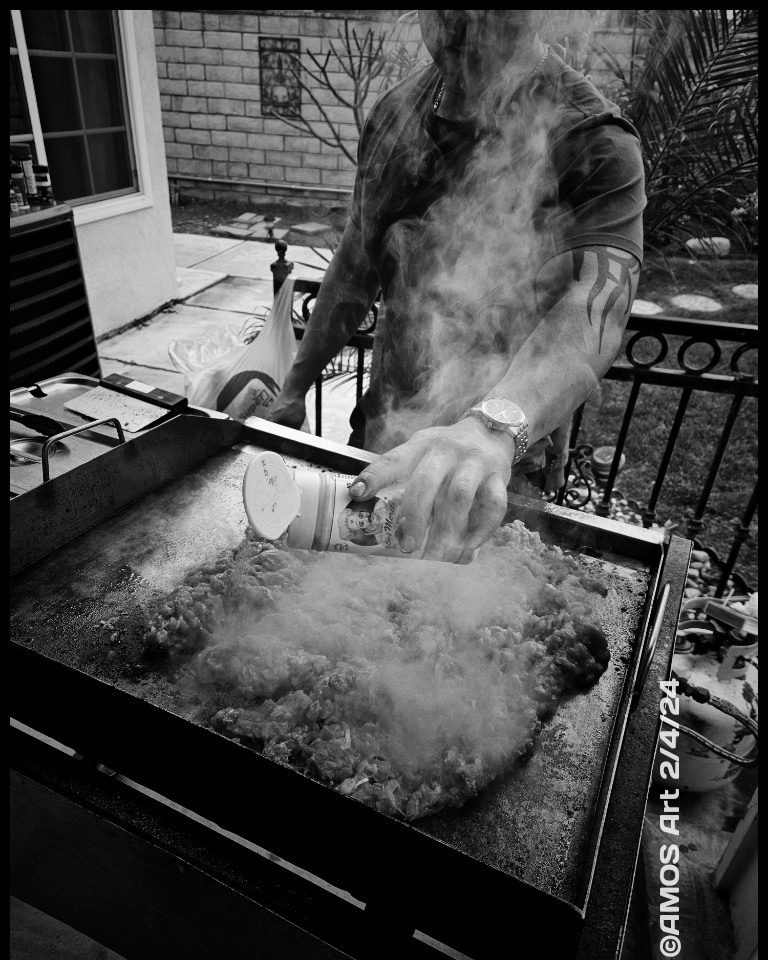

“Well, I like to do the things that I like, but…I enjoy making breakfast, lunch, and dinner. I like to cook. But all I can say about my films, all they have in common, is that I’m the sazón [The ingredients, the flavor, the spice] in all of them.”

Click here to listen to the audio of our Del Toro Interview

Click here to see video highlights of the interview on the SeFija YouTube Channel